The Leap, Part 2

How do we re-invigorate ourselves for our work?

To new subscribers: Welcome! If you’re interested in joining my Lab small-group for writers seeking accountability, inspiration, and personalized guidance as you work on longer-term goals, new cohorts start the first week of every month. Hit the “Message” button for more info.

A little more on what I’m doing here: My goal is to inspire you and to keep you re-inspired.

My fire for writing was quashed, for a long time, and I found ways to get it back. Mostly by shutting out the trends—what’s supposedly good or important or buzz-worthy—and reading and learning from what I consider true quality.

So I intersperse serious craft with inspiration. Because you need both in order to sit down to that most important thing: the daily re-commitment to the work.

—

How do we make ourselves want to write our work?

In Part 1 of this post, I discussed the problem of getting stuck partway through a project—especially a project that we want to finish. Maybe it’s an essay or a short story, maybe a novel or book manuscript, maybe a podcast script or an album. We think it’s worthy, but every time we sit down to the work, our brain shuts off. I can have three cups of coffee and still want to take a nap.

Something internal is getting in the way.

Alice McDermott describes feeling that, “If I could just stick with this damn novel a little longer, it would be finished. The only problem was, of course, that I wanted it to be finished more than I wanted to write it.”

How to get past that block?

In Part 1, I suggested taking “the leap,” or shifting the narrative gaze. You turn the narrative attention somewhere else, break your perhaps-unconscious constraints on what the story is allowed to do or think about, surprise and thus re-energize yourself.

This week, I want to give some examples of the leap. These show how we might re-invigorate our passion for our own work by doing this gaze-shifting ourselves. These models have helped me in very concrete ways to move forward in my own projects, and I think they will help you.

Turn the narrative head

Karen Russell’s book Orange World was the one that most helped me to internalize the concept of shifting the narrative gaze. (I’m always hesitant to recommend Russell for craft advice, for a few reasons,1 but she’s great on this.)

The collection shifts its gaze in essentially every story. I’ll take the example of “The Bad Graft.”

It follows a young couple vacationing in Joshua Tree National Park. One gets overtaken by the consciousness of a tree. (Obviously not in the realm of realism here.) The story goes along describing what happens to this relationship when one party starts craving sunlight and soil instead of RV trips and sex.

Then, two-thirds of the way though there’s a break. And the next section re-opens like this:

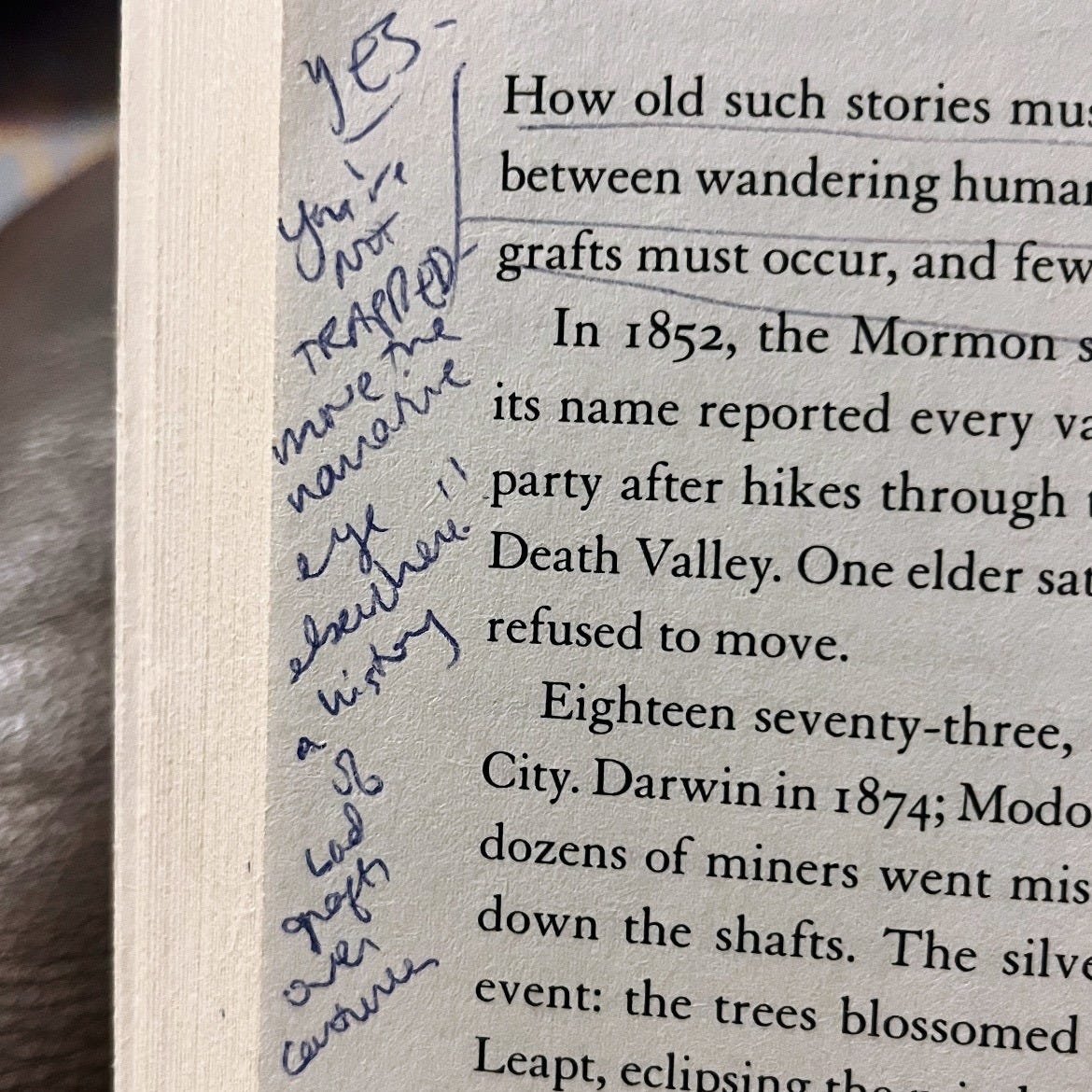

How old such stories must be, legends of the bad romance between wandering humans and plants! How often these bad grafts must occur, and few people ever the wiser!

In 1852, the Mormon settlers who gave the Joshua tree its name reported…

And the next page is a history of the bad grafts over centuries.

My note in the margin of my copy says: Yes—you’re not trapped. Move the narrative eye elsewhere!

After this break for history, the narrative gaze comes back to the main story. But the reader has been re-enlivened.

George Saunders says that, “The reader is a little car. The writer’s task is to place gas stations around the track so that the reader will keep reading. …The writer spends her whole artistic life trying to figure out what gas stations she is uniquely capable of making.”

The writer, too, is a little car when composing our work. We need to re-energize ourselves as we write. Taking these leaps in narrative attention is giving ourselves a gas station that helps us re-fuel.

If you can get your hands on it, Vanessa Cuti’s “Our Children”2 is another great example of a story that lives in the gaze-shift, very close to the end.

Here, a remarried mother in a blended family finally can’t take it anymore. She and the husband abscond together. She imagines what life will be like for the kids if they never come back.

The reader expects this little break into her imagination to go on for a paragraph, then back to the story.

Instead, the fantasy lasts and lasts. We get two dense pages of fantasy, taking the children through the entire rest of their lives, feral creatures up through sexual awakening and reproduction, before we come back to reality. Permanently altered.

On freedom

The takeaway from these examples: You can shift out of scene and action and into exposition and history. You can move from realism to something else, something actually magical or only imaginatively so. To the reader, it doesn’t matter if you “tag” the something-else as mere daydreaming or fantasy. They’ve experienced it either way.

I have no idea whether Russell wrote this little break for herself during the writing process or afterward, whether she did this history break all over the place and had to selectively cut all but one, etc.,

And I have no idea whether Cuti stumbled upon this long fantasy in the course of the writing or whether she planned it all along. (The Cuti, at least, has the feeling to me of having been discovered in the gust of the writing. This is a good thing. It feels fresh, alive, the opposite of what is merely rote or necessary.)

What I know is that, as writers, we can take the lesson as a process note. If your interest for your own story has lagged, throw in what interests you. Abandon your pre-conceptions about what the story has to do, or what it can’t do.

The idea is to solve the problem of having already-written you story, if only in your mind. Even if you don’t know where to go next, this is often actually a problem of having already pinned down the general arc. (Thinking something like: Okay, another page or so of build-up here, then confrontation. Or, Okay, time for the climax.)

An already-written story doesn’t compel us as a writer. An unknown new direction invigorates us.

This technique really has worked for me. Last week, I talked about a story stub I’d written and stalled out on. Breaking for a one-page fantasia into the character’s head cracked open the whole thing.

Reader vs. Writer

I should note that, from the perspective of the reader, it’s especially good to turn the gaze at a point where you’ve earned the reader’s attention and can therefore pause without losing them.

If you’ve gotten your characters to the top of the cliff, pursued by the guy planning to push them off, then at the moment he extends his arms, cut the scene and open on a history of the cliff. Or the main character’s undeclared love for her colleague. Or what’s going on down at the base of the mountain. You’ve got the reader where you want them, so you can afford to cover something else for a bit.

But from the perspective of the writer-in-progress, you’re free to simply turn the narrative attention elsewhere whenever you need to be re-energized for your story. Maybe you wind up excising that part later; maybe you move it; maybe it leads you to a whole new discovery about where the story wants to go or be next, and it never returns to its original course.

The story probably should take some leap, shift its narrative gaze, leave its plane of original conception, if we want to write a story that has weight and sophistication. But it’s best if this leap is not imposed from our knowledge of this principle, and is instead discovered organically from within the story-in-progress, in the process of enlivening our own engagement with the work.

Examples everywhere

I recently watched Dying for Sex on Hulu. I thought it was pretty much a more literal version of Amy Hempel’s story “In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson is Buried.”

But it, too, re-conceptualized itself at the end. The internal monologue of the first few episodes dropped out. It shifted to the best friend’s perspective. It found its footing when it moved its gaze to the less-obvious place: the secondary character as main character.

Once you start looking for the shift in narrative gaze, it’s everywhere.

One last thought: What I learned from Alice Tuesday night

As expected, I came away with brand-new insights from Alice McDermott’s event last Tuesday night, including a simple yet brilliant technique to avoid the trap of melodrama in serious scenes—below the jump.

Speaking of Alice, it’s probably good for me to add a gloss to that first quote of hers in today’s post. (“If I could just stick with this damn novel a little longer, it would be finished. The only problem was, of course, that I wanted it to be finished more than I wanted to write it.”)

For Alice, the solution is adamantly not about finding ways to re-engage her own interest in that damn novel. Instead, she winds up cheating on that novel with a more-exciting new book, one she shouldn’t be writing if she ever wants to finish the first, but one that—perhaps because it’s pure distraction from the real thing—she can’t stop thinking about.

Sometimes, we stall out in our work because it just doesn’t have that fire. Sometimes, abandoning rather than pushing through the stubs of old work is the best way forward.

If you have the energy for a second project in the middle of the first, and the will to finish one of them, then go Alice’s way. But if you find yourself always stalling out by the end of the next project, too, or if something nagging in you is saying, no, this stalled thing has the goods, I just can’t find my way forward, then try to take a leap.

Whatever keeps you going is the right next step.

As for that simple yet brilliant technique: she said

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Craft Lab for Writers to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.