Ask any writer how to improve, and they’ll probably say one thing: Read. Abundantly, widely, constantly.

This is undoubtedly correct advice. For a writer, reading is the only real apprenticeship: we see how other people have done this thing, discover what’s possible, discover that what we thought was innovation is actually old news, discover what feels new and modern within the old and established.

But for the writer, reading is only half instruction. The other half of what we’re seeking is inspiration. We want the books that will move our brain in just the right way to spur our own writing. I often start my new stories and books by writing in the margins of someone else’s. Something about the particularity of their voice jolts mine.

But what are you reading? How do you choose the work that’s worth apprenticing yourself to, both because it’s a worthy teacher and because it’s specifically inspiring to you at this moment in your writing life?

Choosing books

My method is to separate the laminated from the permeable.

At this point in my writing life, the way I choose books is by wandering into a used bookstore or opening a Little Free Library and reading the first sentence. Sometimes the first paragraph. I can tell immediately whether the prose is laminated: if I bounce off, then I put the book down.

If instead the prose is permeable—if I can sink into its first paragraph—then I can almost certainly read the whole book.

I base my choices not at all on what has marketing and publicity dollars thrown behind it. I can basically always tell whether I’ll be able to read an entire novel told in a given voice from the first paragraph. Do I find myself on the second page without even having noticed? Then the work absorbs me. It’s permeable.

Most literature that's erroneously called lyrical today is laminated. It may have a beautiful sheen, but I bounce right off it. It keeps me on the outside.

I want the prose I read to be permeable. I want to be able to sink in.

What makes something permeable?

What’s interesting about the phenomenon of permeability is that it’s hard to analyze. What is it about this prose that pulls me in so thoroughly?

It’s some ineffable quality. It’s not simplicity or complexity, minimalism or lyricism, and it’s not always the same quality across works.

Yet I find it very clear when a writer’s voice is permeable. The “what” is essentially binary: did I get lost in the first page, such that I didn’t even notice I’d reached the second, or did my mind wander?

But the “why” and “how” are harder to pin down. Permeability is fundamentally unlike the craft moves in a story that build scene, suspense, narrative gaze, narrative distance, etc., I can reverse-engineer what the author is up to in those cases.

Permeability is more like obscenity: you know it when you see it.

It’s precisely because of this ineffability that we must make sure we feed our writing minds with the work we find permeable. We are picking up invisible signals, inscribing invisible patterns and rhythms of language in our minds. These are the voices chattering in the background when we are writing our own.

Examples

I want to give some examples from big books that I knew I could read all of, from the very first paragraphs. The very first sentences. The pages fly, totally permeable.

All of these books clock in at around 400 pages or more. Together, they represent thousands of pages of reading. And I knew I could fly through them in a few hundred words.

And please: Feel free to move along from any of these, at any point, if you find them laminated. Use them to hone your own sense of the laminated and the permeable.

This morning Rino telephoned. I thought he wanted money again and I was ready to say no. But that was not the reason for the phone call: his mother was gone.

The eleventh apartment had only one closet, but it did have a sliding glass door that opened onto a small balcony, from which he could see a man sitting across the way, outdoors in only a T-shirt and shorts even though it was October, smoking. Willem held up a hand in greeting to him, but the man didn’t wave back.

In the bedroom, Jude was accordianing the closet door, opening and shutting it, when Willem came in. “There’s only one closet,” he said.

“That’s okay,” Willem said. “I have nothing to put in it anyway.”

Toby Fleishman awoke one morning inside the city he’d lived in all his adult life and which was suddenly somehow now crawling with women who wanted him. Not just any women, but women who were self-actualized and independent and knew what they wanted. Women who weren’t needy or insecure or self-doubting, like the long-ago prospects of his long-gone youth—meaning the women he had thought of as prospects but who had never given him even a first glance. No, these were women who were motivated and available and interesting and interested and exciting and excited. These were women who would not so much wait for you to call them one or two or three socially acceptable days after you met them as much as send you pictures of their genitals the day before. Women who were open-minded and up for anything and vocal about their desires and needs and who used phrases like “put my cards on the table” and “no strings attached” and “I need to be done in ten because I have to pick up Bella from ballet.” Women who would fuck you like they owed you money, was how our friend Seth put it.

Either forswear fucking others or the affair is over.

This was the ultimatum, the maddeningly improbable, wholly unforeseen ultimatum, that the mistress of fifty-two delivered in tears to her lover of sixty-four on the anniversary of an attachment that had persisted with an amazing licentiousness—and that, no less amazingly, had stayed their secret—for thirteen years. But now with hormonal infusions ebbing, with the prostate enlarging, with probably no more than another few years of semi-dependable potency still his—with perhaps not that much more life remaining—here at the approach of the end of everything, he was being charged, on pain of losing her, to turn himself inside out.

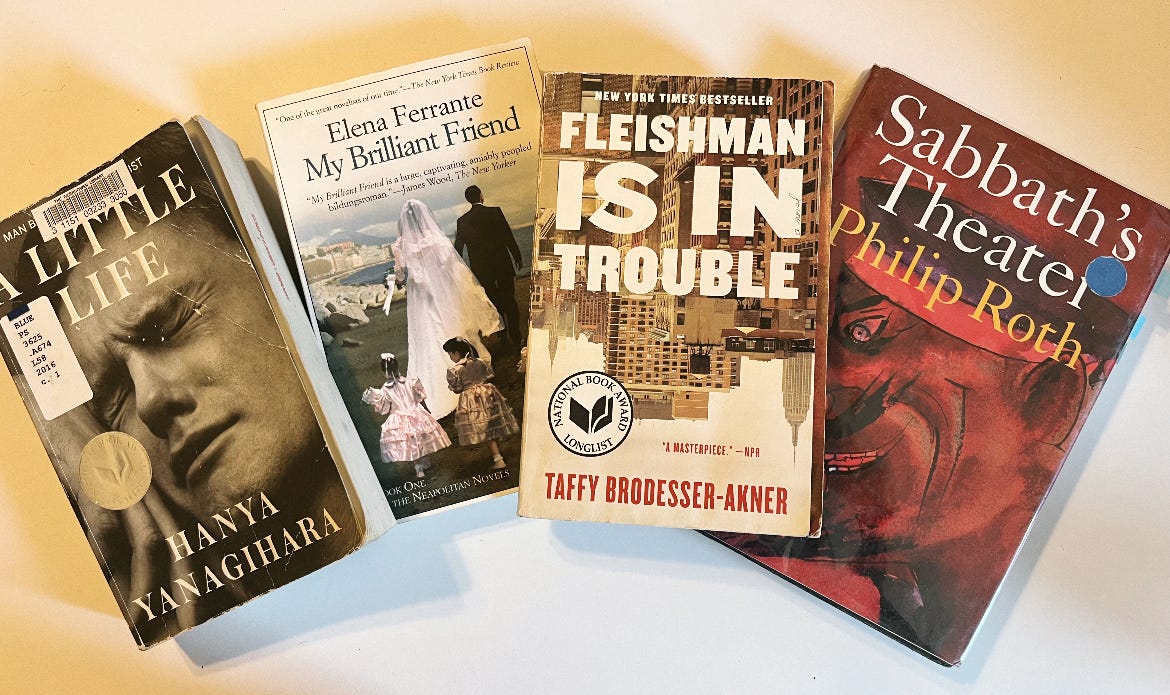

Those are, respectively: 1. Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend (331 pages, though the quartet is 1,693); 2. Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life (814 pages); 3. Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s Fleishman Is In Trouble (373 pages); 4. Philip Roth’s Sabbath’s Theater (451 pages).

Are my examples permeable to you, too, or laminated? Let me know!

The least-good example

I can analyze what makes these openings so good—to a degree.

But I want to start with the least-obviously good one, the one I can’t analyze. For that reason, I think, it contains the most important lesson for a writer.

The Yanagihara—number 2—is particularly baffling to me. When my analytical brain comes online, I do not think this is good prose. I’d call it clunky, over-full of commas. I’d say its pronouns are irresponsibly unclear, “he”s and “him”s whose antecedents, even now, I find difficult to parse.

Yet, as with the others, it passed my test: Before I knew it, I was on page two. This clunky prose had circumvented my analytical brain.

It’s exactly this that teaches me the importance of following my own sense of the permeable and no one else’s. Why do I find that this prose pulls me in, instead of repelling me, when the same defects in another author’s work would push me right out?

I have spent hours on this question. And I simply don’t have an answer. I have to suppose it’s something in the promise, the authority, the authenticity, the urgency of the author. Something on the other side of the prose that I can’t see but I can perceive. Something my writing mind is perceiving even as my analytical mind can’t see it, and that something is a promise the author is making that she can tell a robust story that will be worth my time. I have to trust that’s buried somewhere there in the prose.

A Little Life is one of the most structurally unwieldy books I’ve ever read. I’m typically a structuralist. I have a very high bar for good prose. And I loved the book anyway.

Clearer examples

But the other three examples are clearer to me.

All of them have a voice that conveys absolute authority.

All of them recognize themselves as prose, charting a character’s internal activity.

And all of them suggest that—alongside their humor or their poetry—there’s something deep to be found there. Some weight. Something serious to consider in the voice or the philosophy, the internality of mind.

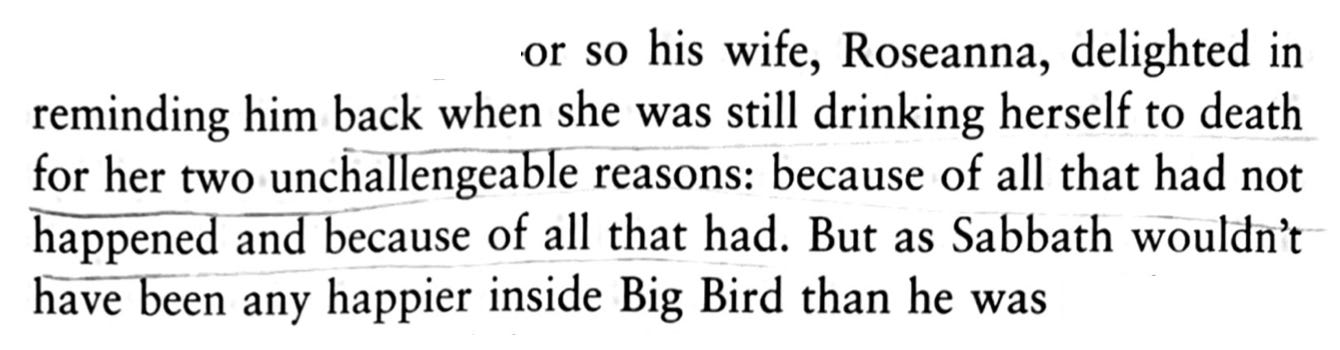

The suggestion of weight in the Roth (example 4) is: “with perhaps not that much more life remaining.”

I’d argue that Roth is the best prose stylist to ever wield the English language, and that Sabbath’s is the book that best proves it—and I discovered him in a Little Free Library in Atlanta. In all my years as an English major and student at the graduate level, I’d never been assigned his books.1 I’ve now read nine of them, and it all started with the permeable voice in the first page of Sabbath’s Theater.

Roth is all but writing poetry in his first sentence. “Either forswear fucking others or the affair is over.” It’s funny and vulgar and unintuitive and sexually irreverent, yes. And it’s also got alliteration and internal rhyme and that biblical “forswear.”

But alongside the poetry, Roth’s prose knows that its first job is to tell a story. It’s aware of the sound of language, it has fun playing with language, but it’s never expending page space purely for the sake of play. This is Roth’s gift: he can write a list of alliterations that’s two pages long, and while he may be giving examples of the same phenomenon, he never repeats the same beat. He deepens the point, shows us other sides of the refractions. Every word gives us something different and new.

(In Portnoy’s Complaint, for example: “For mistakes she checked my sums; for holes, my socks; for dirt, my nails,” etc.)

The top of the next page of Sabbath’s moves from irreverence and humor to a heart-catching wisdom claim: “back when she was still drinking herself to death for her two unchallengeable reasons: because of all that had not happened and because of all that had.”

Roth had me, for thousands of pages of more books, from there.

In the Fleishman example (number 3), the long paragraph ends with an invocation of “our friend.” The previous sentences had suggested a close-third narrative point of view that followed Toby Fleishman. Now, the phrase “our friend” tells me that something else is happening in the perspective, that the book will have a first-person narrator whose narrative closeness and distance from Toby will be a part of the story.

Again, the author is making a promise to me here. She’s a sophisticated storyteller, is what she’s telling me. Just hang on for the ride.

The Ferrante example (number 1) likewise pulls me in immediately. Her opening phone call has the authority of urgency, but it’s the slight undertone of annoyance that comprises the author’s promise to the reader that something interesting will be going on here.

“I thought he wanted money again and I was ready to say no,” says our narrator—and now we have a personality and a relationship already on the page. We have the suggestion of a fullness to the character who feels that annoyance in the face of the news of a death. We are reading for the fulfillment of that rich inner character life.

Subjectivity

Clearly, there’s something subjective in all of this. What’s laminated, what’s permeable? You might agree with my assessments, and you might not. As I wrote in “The Passion for the Job,” what’s important is that we don’t learn to falsify our own sense of the laminated to accord with someone else’s insistence on what good prose is.

Trust yourself in what you choose to read, which is what you will hear in your head when you write. Feel free to put books down.

Of course, there’s a balance to be struck between reading what’s unfamiliar or strange, which can expand our sense of what’s possible in writing, versus forcing ourselves through prose that is simply bad. I don’t mean that you should put down books when you experience discomfort or difficulty, and I especially don’t mean it when that discomfort arises from the subject matter.

What I mean is putting down prose that you know in your gut is bad. Perhaps especially if it’s prose that has been praised as good.

As a writer, everything you read, you learn from. Its voice and patterns live somewhere in the background of your brain. So go ahead and decide to learn from the work that draws you in, that feels to you undeniable, that lets you permeate.

—

Which books are permeable to you? Which are laminated? Do you know why, or do you, like me, find your reasons ineffable? Let me know—

A crime. The male sexual licentiousness in his books must be the reason, but I will die on the hill that Roth’s work is actually feminist. (I say nothing of Roth the person, nor do I care.) His female characters, particularly in Sabbath’s, are some of the most fully realized women I’ve ever read in literature. Maybe his male characters are fill-ins for him, at times; but when his male and female characters argue with each other, the women often win on the merits.

Love the point about the biblical "forswear." That last Roth sentence also invites multiple revisits:

"But now with hormonal infusions ebbing, with the prostate enlarging, with probably no more than another few years of semi-dependable potency still his—with perhaps not that much more life remaining—here at the approach of the end of everything, he was being charged, on pain of losing her, to turn himself inside out."

Those four repeated "with" phrases can be analyzed formally but also work well as psychology, as a litany of complaints pulled from everyday life. The way the last part of the sentence is broken up with commas and more prepositions, making us wait to learn what the charge will be, adds both to the drama and to the character's indictment of himself.

The sentence is conversational and funny, and yet Roth makes us wait on the subject and verb ("he was being charged") as if we were reading Cicero. Not easy to do.

So good, Courtney. I’ve never thought of writing in this way before but it’s absolutely how I judge a book. I agree that there is a certain degree of magic to permeable writing, and I think a lot of it comes down to whether or not you as a reader find it to be an authentic voice. This idea that you instinctively know great writing when you see it resonates so strongly with me. Thanks for attaching words to an otherwise mystical experience.